Blood Relations

Sportswriter Sam Kellerman might have gone even further than his older brother, HBO analyst Max Kellerman, if his generosity to an old boxing friend hadn't led to murder

By Gary Smith

At 9:45 p.m. on a Sunday in the autumn of 2004, Detective Elizabeth Estupinian of the Los Angeles Police Department entered a small apartment just off Sunset Boulevard. On the floor lay a sportswriter beneath a blanket. On his skull were the wounds from 32 blows by a blunt instrument. Against the wall leaned a blood-spattered hammer. The sportswriter's car was missing, and so was his houseguest: a professional boxer with bipolar disorder whose nickname was the Hammer.

It seemed, perhaps, the simplest murder case in Detective Estupinian's 11 years on the job. Unless she happened to be the sort of sleuth who wouldn't rest until she scraped the very bottom of why.

Here was something odd: The victim, just weeks earlier, had written a story about his suspected murderer. Odder yet: a story about his murderer's struggle to control his violent impulses. The detective had only to Google the names of the 29-year-old sportswriter, Sam Kellerman, and of the 31-year-old light heavyweight boxer, James Butler, and up would pop Sam's column for foxsports.com.

Sam wrote of having been in the audience three years earlier when the Hammer -- donating part of his purse that night to families victimized by the 9/11 terrorists -- lost a unanimous decision on national television to Richard Grant ... and then, as Grant reached to shake hands after the verdict, unloaded a bare-knuckle sucker punch that dropped Grant to the canvas unconscious, his jaw broken and mouth spurting blood.

Sam's column described Butler's subsequent diagnosis -- bipolar disorder -- and his comeback after going to prison for four months for the assault. "You ... end up hurting people you love," he quoted the Hammer as saying. "They try to help you, and you flip on them for some small thing.... I've taken the classes, read the books; I know what to do. You can reach a level where you don't need the medication anymore, you just have to be strong-minded." His behavior since the assault had been exemplary. That's what Sam wrote.

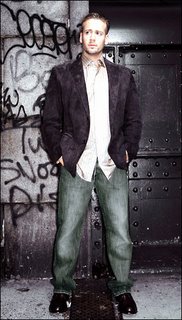

Hold on. If the detective happened to type the names Sam Kellerman and James Butler in the Google box and click on SEARCH, another Kellerman would appear: Max Kellerman, the former host of Around the Horn on ESPN and I, Max on Fox, the HBO boxing analyst, the New York City sports talk-show host ... and Sam's older brother.

On the night Butler cold-cocked Grant, Max was a studio analyst on ESPN2's Friday Night Fights. He begged to differ with his network's blow-by-blow man, Bob Papa, who howled that Butler was "a disgrace to the human race" and with other ESPN colleagues who demanded that the Hammer be banned from boxing for life.

Click. Max wrote a column recommending only a one-year suspension, with a review, for Butler. If one fireman punched another, he asked, would he be permanently deprived of his right to earn a living in his chosen profession?

Click. Max took the Hammer to lunch the day before he entered the gates of New York City's Rikers Island to serve his sentence for the assault.

Click. What? Max and Sam, a pair of Jewish kids from Fifth Avenue, were rappers together before they became sportscaster and sportswriter. The video for their single, Young Man Rumble, appeared on cable television ... with Butler as part of the cast.

If Detective Estupinian wished to solve the riddle of Sam and James, she would have to unravel the mystery of Max and Sam.

Max was Malcolm X. Sam was Martin Luther King Jr. That's what brother Jack said.

Max was Moses. Sam was Jesus. That's what their mother, artist Linda Kellerman, said.

Max taught us to be men. Sam taught us to be human. So said brother Harry.

That's where a writer might start. But a detective?

In the hard drive of the computer at which Sam was sitting when the first blow struck. She'd better not start reading any of the plays, screenplays or stories stored there, because she might not be able to stop. Sam was no dot-com sports hack. He was a self-taught Shakespeare scholar who had directed three of the Bard's plays Off-Off Broadway and written and directed a play titled The Man Who Hated Shakespeare. Nor should the detective lose herself in wonder over the recommendation from one of Sam's teachers at Manhattan's elite Stuyvesant High School:

Ten thousand students and thirty-four years have passed since my first day as a teacher, and I cannot recall one student of this quality, intelligence and talent.... Sam is someone who our world should be proud to know as an example of what humans are all about, and of the heights we can attain. Here he is, Sam Kellerman. The best of ten thousand.

Open this file: Zeida's Eulogy. The speech Sam gave when Zeida -- that's Yiddish for grandfather -- died in 1997. Go to the part where Sam remembers how the four Kellerman brothers used to drop to their knees to massage Zeida's nearly century-old feet as they all watched Yankees games, thinking they were just providing him a moment's relief from his arthritis ... until one day Sam looked at those gnarled feet in his hands and saw the poetry.

These are the feet, he told his brothers, that whisked Zeida to a Gentile neighbor's cellar to hide whenever roving bands of Jew-killers swept through his Ukrainian village. The feet that propelled him across the Dniester River into Romania in 1921 to seek a saner life, that kept him upright when the police there jailed and beat him, that snuck him back home to beg his loved ones to leave, that trudged away once more in sorrow when he couldn't talk them into taking hold of their fate.

The feet, Sam told his brothers, that boarded a ship that took Zeida to Canada, the feet that crept through a forest and across the U.S. border, that carried him to New York City, where he ironed shirts for a nickel apiece until he could open a luncheonette in the Bronx and raise his only child, Henry, who would become a renowned psychoanalyst and buy two apartments on Fifth Avenue so he and Zeida could live as relatives did in the old land, a few steps apart.

The feet that took Zeida to his bedroom to sob the day the letter came informing him that his mother, sister, brother-in-law, nephew and niece had been rounded up by the Nazis along with thousands of other Jews and herded to the edge of a ravine, the Yevpatoriya Ditch, where they were machine-gunned and covered with earth, which writhed until the sun rose the next day.

But what had that to do with the crime scene confronting the detective?

If detective Estupinian wished to learn how a psychologist's son from Greenwich Village ended up beaten to death by a boxer from Harlem on the other side of the continent, she would need eyes, like Sam's, that saw beneath the skin. The skin on the left corner of Max's lips, for example, the faint disfiguration she'd notice if she scrutinized his face on TV. The scar that once was a blazing welt....

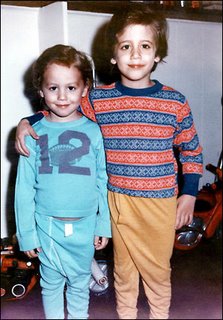

Max was three years old. He had just discovered Batman and deputized two-year-old Sam as Robin. For years they would patrol their apartment in their Dynamic Duo costumes, relentlessly droning the old TV show's theme song -- na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na, na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na, Batman! -- until suddenly evil appeared and they'd hurl themselves at it, punching and kicking it into submission.

One day evil entered their home disguised as a clock. The clock, which changed colors from red to pink to blue, was their father's anniversary gift to their mother. Because Max grew up in a house ruled by a psychoanalyst, he could tell you by the time he reached puberty that he despised that clock because it was a gift to the mother who, he felt, had betrayed him by turning her attention to Max's baby brother: blue-eyed, blond-haired, charismatic Sam. And so Batman convinced Robin that the clock must be destroyed. Max jerked on the wire while Sam bit it, to no avail. In his fury Max sank his own teeth into the wire, and all of a sudden -- zap! -- he saw zebra stripes and smelled something funny. The burn fused the left sides of his lips and required three surgeries. What would've been, their mother still wonders, had that accident never occurred?

Max entered first grade. His scarred lip made him a target. He told his mother about a boy who was taunting and poking him in the schoolyard. Tell your teacher, she said.

Max's father heard the conversation. Two responses lay coiled in Henry's genetic wiring. You could ignore the threat and hope the local authorities would protect you, as Zeida's mother and sister had done. Or you could attack your antagonist, the way Zeida had as a teenager in Ukraine, cracking the skull of a Jew-baiter with his own walking cane, then landing a left between his eyes, dropping him in a pool of blood. The way Zeida's brother really had, capturing two Jew-killers in the dead of winter, their shirts still red with neighbors' blood, then marching them onto the frozen Dniester, ordering them to cut a hole, then shoving them into it and covering the hole with the disk of ice.

Henry, as a child, became a wunderkind of the Jewish leftist movement, performing dramatic recitations of resistance poems in Yiddish across the country. The essence of this poetry was: the Holocaust, never again.

Henry pulled Max aside. Next time the kid pokes you, the psychoanalyst told his scrawny first-born, slug him in the face with all your might. And that would go for anyone who picked on Sam, Harry or Jack, as well, because Max was his brothers' keeper.

Max unloaded. That kid never taunted or poked him again.

As this the way life worked? One circumstance leading like an arrow to the next and then the next? If it were, then a forceful and logical man might begin to foresee those circumstances, might blaze his own trail of cause and effect ... and determine his fate. Max began to sharpen his power of reasoning, to strip the sentiment from an argument and make it stand on the legs of logic, knowledge ... and will. The dinner table became his workshop. Pick a topic. Any topic. Hakeem Olajuwon, best center in basketball? How can you say he's better than Patrick Ewing? Didn't matter what the conventional numbers said; Max unearthed factors that nobody else at the table knew, debated in a way that made you feel he'd already rifled through the closets and drawers of your argument and discarded it. He became an animal of logic. That's what brother Jack said.

One boy kept entering the animal's lair. Sam, as a fourth-grader, wrote a story about a monkey in a barrel whose keeper pelted him with numbers -- big, heavy ones like 110 -- until the monkey heaved back a huge one, 1,186, the sum of all the numbers hurled at him, and knocked out the shocked keeper. All the brothers, as sons of a shrink, knew it was a story about Sam and Max. Sam could think and articulate as fast as his big brother, lie in wait listening and then wreak havoc with a reply. Once, debating why man had invented sports, Sam unloaded this haymaker: "Sports is man's joke on God, Max. You see, God says to man, 'I've created a universe where it seems like everything matters, where you'll have to grapple with life and death and in the end you'll die anyway, and it won't really matter.' So man says to God, 'Oh, yeah? Within your universe we're going to create a sub-universe called sports, one that absolutely doesn't matter, and we'll follow everything that happens in it as if it were life and death.'" Which delighted Max, because he craved a foil, someone who would compel him to hurl ever bigger and heavier numbers.

On a dry debating day they'd resort to the King of All Games, a joust they'd invented in which they'd select a subset -- condiments, say -- and then hammer out its hierarchy, haggling over whether salt, butter, mayo or ketchup was the king, the prince or a mere jester. Then they'd analyze each other's analyses, exposing hidden psychological motives, louder, louder, with younger brothers Harry and Jack chirping from the sidelines, until their father would shout, "Time out! Time out! I can't take it!" and their mother would flee to her easel and their friends would flee to the bathroom, choking back laughter, leaving Max and Sam at the table arguing, their debate disintegrating an hour later into Ahhh, you're full of s--- and You're such a f------ moron! ... two boys growing closer than any brothers you've ever known.

Few opponents kept coming after Max and his scarred lip. He sat beside his dad one night and watched Muhammad Ali fight on TV. He disappeared into his bedroom with Ali's autobiography and emerged spouting Ali's poetry. He decided at age eight that he needed more control over his response to his antagonists, more science -- Ali's science. His father started taking him to a gym for boxing lessons, which lasted until Boom Boom Mancini battered Duk Koo Kim to death on national television in 1982. The boy's horrified mother and grandmother retired him at age nine.

Max stomped ... then sulked ... then sublimated. If he couldn't be a boxer, he'd be a boxing know-it-all. He began memorizing five boxing magazines a month, reading them during classes at Hunter, the hotshot public high school he tested into in seventh grade. He compiled lists all day, the more obscure the better: Top 10 left jabs. Top 10 middleweights of 1986. Top 10 middleweights of 1968. He turned his living room into a ring, with a cooking timer to ding out the rounds, and began tutoring his three brothers, all within six years of his age. At 14 he was sneaking back up those grimy stairwells into boxing gyms and writing to Bundini Brown, asking Ali's shaman to train him to the world title while Mom wasn't looking.

One Sunday, just after he turned 16, Max was watching Boykin on Boxing on a Manhattan public-access TV station. He turned to his dad. "I could do that," Max said. His father and grandmother Esther had schooled Max, Sam, Harry and Jack in public speaking from the day they'd begun to babble. "Of course you could, Max," said Henry.

Four days later he took Max to the Manhattan Neighborhood Network studio and paid the $27 studio fee for a half-hour slot. The engineers pinned a microphone to Max's lapel, seated him in front of a camera and flashed a signal. Off he soared, making references to fighters from a half century before he was conceived, sorties into the psyche of Mike Tyson, allusions to Sophocles and Star Wars. All the phone lines lit up within 30 seconds. When he walked off the set, the engineers applauded.

"Tyson could whip Marciano, Louis and Dempsey in the same afternoon!" Max would crow, his big, expressive eyes sparkling and his thick, dark eyebrows hopping with each feverish opinion. "I don't think that's an opinion! That's a fact!" Lowlifes and Columbia professors called his weekly show, Max on Boxing. So did Dustin Hoffman, who asked Max to his house for dinner. David Letterman had Max on his show. The kid became a Manhattan cult phenomenon.

Max's World, his friends called it, a planet where a kid could proclaim that he was going to do the implausible -- then do it. Sam, Harry and Jack, swept by the gravitational pull, followed Max to the studio each Thursday, learned the control room and assumed production of the show, which would last nine years. Sam Kellerman Live and Jack Kellerman Live would follow when Max moved on.

MaSaHaJa Inc., the brothers called themselves in the credits. It was the name their father had coined when they were little boys dragging and jamming their mattresses into one room while three other bedrooms lay vacant, staying up past midnight plotting the tribal raid they'd spring on America's media and entertainment giants, and the riches they would reap. Their ambition was a demand for justice: Their successes and rewards would vindicate all that Zeida had suffered. Their mother's belief, borrowed from a Buddhist monk, that all a man needed was one bowl, one shawl, one roof? Sorry, Ma. It never had a prayer.

Their Yiddish lessons made them feel as if they were the guardians of an ancient tongue on the verge of extinction. Each Saturday morning, on their way to the secular Jewish school that their father and his friends had founded, the four mop-haired boys would walk side by side. They were closer than brothers -- more like survivors huddled together. That's what Max's longtime friend Steven Schneider said. They'd drop everything and come on the double whenever one of them called a Brothers Meeting. They'd play hooky and go to the movies en masse, kiss and caution one another when they parted. Walk into their home, and you couldn't help but smell the blood loyalty, the certainty that these boys were going places ... together, like fingers in a fist.

And so, of course, Sam had to climb the same grimy stairs as Max. All that Sam and his two younger brothers had ever had to do when they felt threatened was run to a phone, and Max would appear like an avenging angel, his Little League Reggie Jackson bat tucked in his jacket sleeve in case their enemies outnumbered his fists. But Max had just left for Connecticut College. Now it was Sam's turn to make sure that no Kellerman ever again became a victim.

In his senior year Sam climbed to the third floor above the Greek deli and the tailor shop on Times Square. He heard the machine-gun fire of the speed bags beyond the open steel door. He peered into Max's World ... and stepped inside.

Times Square Athletic Club wasn't where you'd look for a 5'8", 130-pound kid with a perfect 800 on his verbal SAT. Sam, to be honest, didn't really want to wallop anyone. He was the brother who'd sit and listen all day to old people whose loneliness and complaints annoyed everyone else, then walk them down Fifth Avenue with slow and tiny steps. The one who'd leap into the middle of a family fray and point to something so poetic and noble in each combatant's cause that both would feel as if their conflict had occurred in a play crafted by a master, and that resolution was aesthetically the correct choice. He was the Kellermans' glue.

Sam approached the boxing ring. Inside the ropes stood a black man two years older, five inches taller and 30 pounds heavier than he, cannonball shoulders throwing thunder at a sparring partner. Trainer Alexander Newbold, a strapping man from Harlem better known as Ness, suddenly turned to the newcomer. "Got your mouthpiece?" he barked.

Sam froze. "Why?"

"You boxin' him next."

"No way! Man, that guy can punch!"

Yes, he could punch -- James Butler had just won the first of two Golden Gloves titles. He could kick, too. The first time Ness laid eyes on him, James was kicking in the glass door at a fast-food joint at 155th Street and 8th Avenue whose owner had just given him the heave. He was a teenager from the Harlem projects -- absent father, party-loving mom -- who had served time for petty larceny. "Kid, you should be boxing," Ness told James. "You got a lot of anger in you."

James showed up at the gym. He looked as if somebody had just stolen something from him, and it might've been you. That's what trainer Bob Jackson said.

"You think I could hit like the Hammer?" Sam asked Ness.

"People are born with that pop," said Ness, "but I'll teach you balance and defense. You won't get hurt ... unless you're chicken."

"I ain't chicken!"

Sam joined Ness's boxers and, like the Hammer, basked in the nickname he got from the trainer: the Baby-Faced Assassin.

An older kid jumped brother Harry at school. Sam called Max at college for advice. "All depends where you see yourself in the food chain," said Max. "Are you predator or prey?" Sam bloodied the kid's face. Damn, Sam was tough. He got into a scrape with an Albanian punk, opened a gash in the kid's head, then raced into a deli, grabbed a fistful of napkins and got down on the sidewalk to stanch the kid's wound and comfort him. No matter how well he learned to use his fists, Sam was still the boy who, every visitors' day at summer camp, had gone straight to the sister of a fellow camper -- the girl whose face was discolored a shocking pink -- to sit beside her and lean so close, with such warmth, that she always lit up. The kid who identified with the victim, the outsider.

So, of course, Sam's heart went straight to the brooding Hammer. But James kept his distance, suspicious of Sam's charm. What could a dropout from the projects have in common with a Shakespeare scholar?

It wasn't that Max condoned the casual violence he'd begun scribbling about in his bedroom and rapping out on street corners. How could he, after what his family had been through? Rap was just a genre, Jack, like the Jewish partisan songs he and his brothers sang in Yiddish, or the soliloquies from Antony and Cleopatra that Sam recited. Another way to explore old Kellerman terrain: the quicksand between weakness and strength.

Max rented an apartment on West 110th Street in 1994, after leaving Connecticut College behind for Columbia, and turned the place into a music studio. Soon Sam was at Max's elbow, wordplaying for all he was worth in that detached Hebrew hip-hop hitman persona he created for his rap and TV audiences. Sam too was going to Columbia -- well, occasionally -- having chosen to devour all 37 of Shakespeare's plays on his own rather than in a classroom. Off the two brothers would stroll, ball caps on backward, ending up on a corner or in a park among strangers giving each other the eye. You spit? somebody would ask. Yeah. You spit? And suddenly a circle would form and a rapper would start kicking rhymes until a challenger took his place. Max could get ooohs and ahhhhs in the circle. But Sam could make the circle bust up, fall out: Oh s---, you hear that white boy spit?

One day Sam suddenly started rat-tat-tatting homemade verses at the gym.

Don't waste a single tic

With a clever little quip

Like a stupid-ass villain in an action flick

Give me just enough time to react and flip

Shoulda done me when you had me, dick

I'll gladly rip any rapper in half

Like a bad first draft....

Say what? Scrawny smart white boy from the Village could gush rhymes like he was turning on a faucet. In the midst of one spray, Sam slipped in a ringer.

"That line ain't original!" cried the Hammer. "That's Pac! Tupac is my man!"

They laughed. Sam and the Hammer had found a common language. They began heading down 42nd Street after training sessions, window-shopping, hip-hopping, the playwright and the pug. At Sam's side James became the man he wanted to be, the curious and sensitive guy who planned to spend his days after boxing helping at-risk kids from broken homes, kids like him. He'd watch Sam's acts of generosity -- giving meals and even the shirt off his back to the homeless and, years later, directing a play to raise money for the families of the 9/11 victims -- and he'd be inspired to give part of a $20,000 fight purse to the same cause.

One day Sam -- who loved women and the words that made women melt -- decided to melt one for his pal, talking up James to a girl they'd just met. James wanted no part of Sam's setup. Suddenly Sam was staring into two glowing coals where his buddy's eyes had been. "Man, I hope James never snaps on somebody," Sam told Ness. "He's like Tyson." But it didn't scare away Sam.

So when Ruffhouse Records, a label of Columbia Records, offered to produce a single and a video of Max and Sam's Young Man Rumble -- just another day in Max's World -- Sam asked the Hammer to appear in it. James showed up, grumbled over the long hours and lack of pay and left before the shoot was done.

Max began to sour on Sam's buddy. Still, for Sam's sake, Max stood up for the Hammer on TV and in his espn.com column after James sucker-punched Grant, then took the Hammer to lunch to encourage him.

Max wouldn't tell his brother to stop reaching out to a troubled soul. That would be killing the best part of Sam. But there was more to it than that: As long as Sam's selflessness existed in the world, Max was free to charge toward his goals, to cash in on his talent. In tandem they could solve the paradox in their blood -- kinship with the weak and insistence on strength. They shared one consciousness and knew they couldn't be beaten, because each of them was two people, while everyone else was one. That's what Max said.

A love that complicated, of course, mired Max in a quandary. His duty as crew chief of MaSaHaJa, keeper of the Brothers Kellerman, was to jam his foot in the doorway of the American dream and keep it open long enough for SaHaJa to blow in and take over the control room. How could he fully relish his success as long as Sam was writing books and screenplays that he showed to no one, directing and acting in plays in front of a few hundred people to raise money for the bereaved?

One day a shelf full of chess books in the library at Columbia caught Max's eye, and he devoured this new game the way he had boxing. The universe was too vast and unruly for a man of logic to control. But a chessboard, like a boxing ring, had rules and parameters within which cause and effect could be tested, demonstrated, controlled.

Max's career became a chess game. He pored over it, searching for the move that would maximize his -- and his brothers' -- advantage two or three moves later. In 1998 he parlayed a highlights reel from Max on Boxing into a job as cohost of ESPN2's Friday Night Fights. He was good. Very good. Decibels and decimals, his family's dinner-table debates in front of a camera. Three years later, at 28, he flew to Los Angeles and strode into a roomful of executives at Brillstein-Grey Entertainment, moguls who steered the careers of Brad Pitt, Nicolas Cage and Adam Sandler and who thought this hotshot young boxing analyst had come seeking guidance in his field. "I have no interest in continuing in sports," Max informed them. "I want to be starring in a feature film in 12 months and accepting an Oscar in a year and a half. And the real reason you'll want to work with me is that then you'll get to work with my three brothers. Just wait until you see what they can do." After raving about Sam's writing and acting skills, Harry's prizewinning short films and Jack's wizardry in musical production, Max turned to a Jewish executive and began speaking Yiddish. Then he left, and everyone just sat there, blinking.

Michael Price, a talent manager dazzled by the performance, knew he had to harness the performer. You, he told Max, could make so much money in broadcasting that you could produce your own movie one day and star in it, so why spend 10 years starving in audition lines? Max saw the logic, and in no time the two of them parlayed his boxing cameos on Pardon the Interruption into a role as fill-in host on the show, parlayed that into a job hosting his own show, Around the Horn, and then turned that into a blockbuster deal to host I, Max on Fox. Everything he plotted ... worked. A man could take hold of his fate.

Funny, what happened one evening in 2003. Max entered Price's office in Hollywood to sign his two-year, $1.66 million deal with Fox. Sam came along to ink his first contract: a $4,600 deal to write 23 columns for foxsports.com, which Max had helped arrange. Price watched in astonishment: Everything was upside down. As Max hastily scribbled his signature in silence, Sam shouted, "Everybody stand back! I'm about to sign my contract! Wait a minute! Photograph!" Sam struck a bonus-baby signing pose, then swaggered out of the office. Max hurried to catch up to him and kiss him on the forehead, his eyes misting with so much pride in his brother's achievement that Price, for the only time in his life, felt cheated to have been an only child.

Here, though, was Sam's quandary: Big brother's credit card in his wallet. Big brother's car in his name. Big brother's fist knocking on corporate doors for him. Big brother's shadow everywhere he turned.

Shaq vs. Kobe: best player in the NBA? Max argued every day and twice on Sundays for Shaq and Sam for Kobe, both knowing, as sons of a shrink, that Shaq was Big Brother Archetype and Kobe was Little Brother Archetype and that they were really arguing Max vs. Sam. And that Kobe had to shove away Shaq, had to prove he didn't need Big Brother to make it big ... just as Sam needed, at least for a while, distance from Max. So the most shocking and most natural thing occurred in February 2004. Sam bid the Brothers Kellerman farewell and moved to L.A.

On Sept. 13, 2004, just above latitude 15¼ north in the mid-Atlantic, easterly trade winds converged and began to rotate counter-clockwise, forming a tropical depression. Jeanne, the second hurricane to target the southeastern coast of Florida in three weeks, started to chug northwestward. James Butler, working as a sparring partner in the Catskills, decided that he could not go home to Florida.

He had just weathered Hurricane Frances in Vero Beach, where he'd lived for nearly a year. He'd delighted aid workers at the shelter where he stayed with his girlfriend, their newborn son and his girlfriend's daughter, ferrying bucket after bucket of water to flush the toilets. But the storm seemed to trigger the mood swings and sleeplessness of his manic depression. He'd left Florida on Sept. 7 and headed to upstate New York.

He needed money. He needed a fight. He needed a place to train where no power lines were down. He'd gained more than 70 pounds during his four months in jail while taking a cocktail of medications for bipolar disorder that made him feel sluggish, then -- after dropping much of the weight -- lost two of his four bouts in a lackluster comeback. His relationship with his girlfriend was hitting the rocks. His relationship with his new trainer in Vero Beach, Buddy McGirt, who was busy with other fighters, was over. All the Hammer had was talk of a possible fight in California, a career swirling down the drain and almost nowhere to turn, except....

Sam's phone rang. His own career had begun to take off since his move to Los Angeles. He'd acted in commercials with Willie Nelson and Christina Aguilera. He was in talks with MTV2 about hosting a new call-in show. The producers of the HBO series Entourage were so taken with him that they kept calling him to the set, trying to figure out how to work him into their show.

The closer Sam came to finding himself, it seemed, the more he needed to preserve those 2,800 miles between himself and Max. He might let a week pass without calling his brother, and Max, sensing Sam's need, might do the same. Just a few days earlier, after Max had flown to L.A. on a business trip and squeezed in a night of boxing and a few rounds of the King of All Games with his brother, Sam had stayed home for the evening to write rather than drive Max to the airport. Sure, it had stung Max a little, but hadn't every pair of brothers known a time like that? "Don't worry about me," Max urged him. "Let your talent fly. Just let it fly."

L.A. was Sam's liberation from the all-nighters writing term papers for his New York pals, from editing every word his brothers wrote and serving as the family glue. L.A. protected Sam from Sam, freed him to let it fly. His success there was inevitable, because in a town full of people who stand out, he stood out. That's what TV producer Mark Neveldine said.

But now, on the other end of Sam's phone line, came another voice from New York, an old friend. James needed a place to bunk for a few days, a new gym -- perhaps trainer Freddie Roach's place, not far from Sam's -- and a new start. Sam already had a guest in his cramped apartment, an aspiring actress from New York named Beatriz Quiñones. But he'd just written a column for foxsports.com asking the world to give the Hammer another chance, so how could he not?

James arrived and sacked out on Sam's couch. A few days became a few weeks. James grew jumpy. He didn't like L.A. He wanted to go home and hold the newborn son that he hadn't seen in five weeks, the one he couldn't bear to see grow up without a dad, as he had. One moment James seemed depressed; the next, so excited that the words tumbled from his mouth. But he wouldn't take his medication, which had made it so hard to train. He sat in front of the TV, making it hard for Sam to write. They began arguing over little things. Beatriz felt the tension growing, packed up and cleared out.

Sam called Max on Oct. 6. Maybe it was only to argue Kobe-Shaq. Maybe it was just to dissect the Yankees-Twins playoff game that night. Max will never know. He was at Yankee Stadium, and the crowd's thunder drowned out Sam's voice. "I can't hear you, Sam!" shouted Max. "Talk to you later!" But he got home late and didn't call back.

Five nights later another young actress, Claudia Salinas, went to dinner with Sam and returned with him to his apartment. James was watching TV again. "I need to watch a game for the column I'm writing," Claudia remembered Sam saying. "Can I change the channel?"

"No," said James.

"Yo, I've got to work," said Sam. "I've got to see who wins so I can finish this story."

"Wait till the commercials," growled the Hammer. It almost seemed as if he needed to know whether even Sam would push him away.

"Let's take a walk," Sam said to Claudia. He was in Kellerman quicksand: trying to help a victim who was making him feel like a victim in his own home. "It's like this all the time," he told Claudia. It was time, Sam decided, to say no, to ask James to leave.

Sam, according to police, was sitting at his computer the next day when the Hammer struck. He'd once told a friend that if a larger man ever attacked him, the man had better be ready to fight to the death. Was that why Butler's hammer struck 31 more times? Or was that just the mathematics of rage and disease?

A $300 postal money order to pay for James's flight back to Florida -- sent by his boxing manager, David Berlin -- arrived in Sam's mailbox that day.

Four days passed. Why, Max and his brothers wondered with growing alarm, didn't Sam answer their phone calls or e-mails? Max twice asked his friend Steven Schneider, who had moved to L.A., to pay a visit to Sam's apartment. Both times the blinds were drawn, and Steven's knock on the door went unanswered. On the second visit Steven slipped through a window, froze, then staggered away to make the grimmest phone call of his life.

Three days later James Butler called the LAPD from UCLA Medical Center's psychiatric facility, where he'd gone in Sam's car seeking a support group for manic depression. He told police that he'd gone for a short walk a few days earlier, returned to find Sam dead and felt so distraught that, rather than call the police, he'd drunk a bottle of wine, filled the bathtub, slit various parts of his body with a razor blade and lain in the water, hoping to bleed to death. He couldn't remember starting the fires that left ashes and two circular burn marks in Sam's bedroom carpet. He was innocent, and Sam was his only ally. That's what James told Detective Estupinian.

Grief leveled Max. It laid him flat on the earth beside his brother's open grave. He rose somehow and set his jaw to the task of joining his brothers to shovel the dirt on Sam's coffin rather than leave that to a stranger. Then they walked away, vowing that the three of them now must do the work of four.

But it was harder than Max had imagined. For a few days or a few weeks, any man might suffer the sobbing and sleeplessness, the shaking and shallow breathing and the blood rushing so hard to his brain that he has to put his head between his legs to remain conscious. But the weeks became months, and Max's friends and relatives feared for his career, his new marriage ... and then for his life. "Don't let this be a double homicide," his pal, producer Bill Wolff, implored him. "Don't let this guy kill you both." He missed 12 days of his show, I, Max, and then, with the crew in tears watching him attempt to compose himself on his first day back, somehow got a half hour onto tape. Fox canceled the struggling show five months later, and Max barely cared. Without the two antidepressants and two antianxiety medications he took daily for a while, he wouldn't have cared if sunlight never reached the earth again.

Max was too busy haunting the trail of cause and effect, shouldering should'ves and if-onlys. If he'd never set a foot in a boxing gym, Sam never would've met Butler. Max should've never gone to bat for Butler's right to resume his career. Should've insisted that Sam not let Butler into his home. Should've called Sam back the night the phone rang at Yankee Stadium. Should've never relaxed his vigilance as his brother's keeper, no matter how much space Sam wanted. Max could not let himself off the hook. The only way he might ever do so was perhaps the most frightening: to concede that he wasn't in control. That it's only if you look backward, as detectives and storytellers do, that circumstances align, one leading to the next.

Redemption? Sorry. Still too early. No saving truth yet for Max. No baby Sam born yet to Max and his bride, Erin. No satisfaction from the 29-year prison sentence meted out to Butler last week in L.A. after his guilty plea to voluntary manslaughter and arson.

Last October, on the first anniversary of Sam's death, Max went to the cemetery on Long Island and stood over his brother's grave, next to Zeida's. Stood there wishing like hell that he could talk to Sam about this strange new world he inhabits, eerily similar to the one Zeida escaped, where Irrationality trumps Rationality in the King of All Games.

1 comment:

Nothing but respect for Max and the Kellerman family. RIP Sam

Post a Comment